Intellectually, I expect the milestones to hurt. It is April and I am watching the city yawn itself awake from winter. Magnolias remind me that apartment buildings have front yards. I warn my boss that I have an intense few months ahead of me. We are sitting in a room with white boards for walls. April 15th, I tell him, what would have been my mama’s birthday. Then mother’s day. Then her anniversary in June. I don’t know what I want my boss to do with this information but I do know that I want to be a whole person when I sit on the sixth floor of my office and type excel formulas at my desk. I want to be a whole person and I know now how the self can fracture, falter in the forward motion of loss.

It is April and I go to a Passover seder at a friend’s East Village apartment. The friend has pushed two tables together, one round, one rectangular, in the center of the living room and draped them in white cloth. Two sloped triangular gaps form on either side of the spot where the tables touch. All night we are careful not to place our wine glasses there. During the seder, we go around the tables and say what we are hopeful for. I hear myself say it again. I have an intense few months ahead of me. This is a weird answer to the prompt and I feel its weirdness get stale in the air of the room. I am not sure what I am hopeful for. I am grateful when it is the next person’s turn to speak.

So much of the second year of grief is spent bracing. I tell myself I’ve done this once before. That I know what it feels like to splinter. That I know what it feels like to be here and there, on the sixth floor, on the back porch, typing excel formulas, talking to hospice nurses, scooping office Goldfish crackers into small paper cups, choosing flowers for the service, dipping parsley into saltwater, my pinkie into wine, stroking the skin behind my mama’s ear on the day she chose to die. I am braced for fissure, obsessed with incongruity. All night I stare at the gap where the tables fail to touch.

It is April. It is the day before the day that would have been my mama’s birthday. I think maybe I was hopeful I could pad myself in knowledge. Hopeful I could acknowledge the season, the magnolias, the unconscious clocks of our bodies and worlds. Hopeful that if I could know it and I could name it, the way that months can hurt us, then maybe these months wouldn’t hurt me quite as much.

I wake up. It is April 15th. I can not comprehend the extent to which I am undone.

My mama always used to eat the top off of her corn muffins first. Down the block from my childhood home is a bakery called Palmer’s. They sell these perfect corn muffins, the kind that manage to be light and hearty all at once. They’re topped in flakes of sea salt. Those are the best bites, the ones from the top of the muffin where you get the firm lip of its edges, its sweetness cut by a flake of salt. My mama used to cut her corn muffins in half horizontally, so that one half was the top of the muffin, the other half the bottom. I used to watch her eat the top half first.

This baffled me. One half of her muffin was so unequivocally better than the other half and then she’d eat the good part it and it would be gone. I was sure I had a more equanimous approach, I’d cut my corn muffins vertically so that each half had a little of both. I don’t have some big metaphor here. I’m not saying that my mama had it right, that we should eat up all the good in life because we never know when it will be gone. I still cut my corn muffins vertically. I’m just trying to explain what it feels like to miss a whole person. I’m just trying to understand where the way that a person eats a corn muffin goes when they are gone.

After my mama died, a friend of hers planted 150 allium bulbs in her honor in the front yard of my childhood home. Have you ever seen 150 allium before? Allium are Seussical. They are other worldly. They are purple pompoms that stand four feet tall. They are a totally unreasonable thing to plant 150 of in your front yard. Last spring, our yard was a surrealist landscape. I waded through the tall green stalks.

It is April and once again the allium are peaking their heads above the ground. I see them when I go home to my childhood home for what would have been my mama’s birthday. I want to lay on the ground and whisper to them that we have an intense few months ahead of us. I want to ask them questions about clocks and all the things a month can hold. I want to know how they know when it is time to bloom. It’s such an incongruous image, 150 allium in a suburban front yard.

On my mama’s birthday we eat her favorite corn muffins for dinner. We cut them vertically because I still want each half to have a little of the good stuff. We heat them in the toaster, spread on butter and blueberry jam. I know I want to be a whole person. I know I want to miss a whole person. I can’t stop thinking about incongruity, its relationship to wholeness. Does incongruity negate wholeness or necessitate it? I want to place my wine glass in the gap where the tables don’t touch and watch the liquid fall.

Hi friends <3

Thank you so much for reading. It feels like whenever I try to explain how much it means to me that you would take the time to do so, I fail to get it right. Time is arguably the most precious and finite thing we have. I am so outrageously honored that you would spend some of yours with my words.

To that end, I wanted to share a little writing win with you all. Last year, an essay of mine, “On Molting,” won The Kenyon Review’s Short Nonfiction Contest. This was one of those this doesn’t happen to real people moments. It still feels like that to me.

“On Molting” was the first essay I wrote after several months where writing felt impossibly hard. I wrote it in a class with a teacher that I love. It’s a weird experimental essay that is sort of about grief and sort of about having a threesome and sort of about riding the subway. I assumed it would live on my laptop.

A few weeks after the class, I saw on Twitter that one of my favorite authors, Melissa Febos, was judging the upcoming Kenyon Review’s Short Nonfiction Contest. I’d only written one essay in the past several months and it was a weird one. I submitted it on a whim.

I never considered that this essay would win (or processed what it would mean to publish an essay about having a threesome lol).

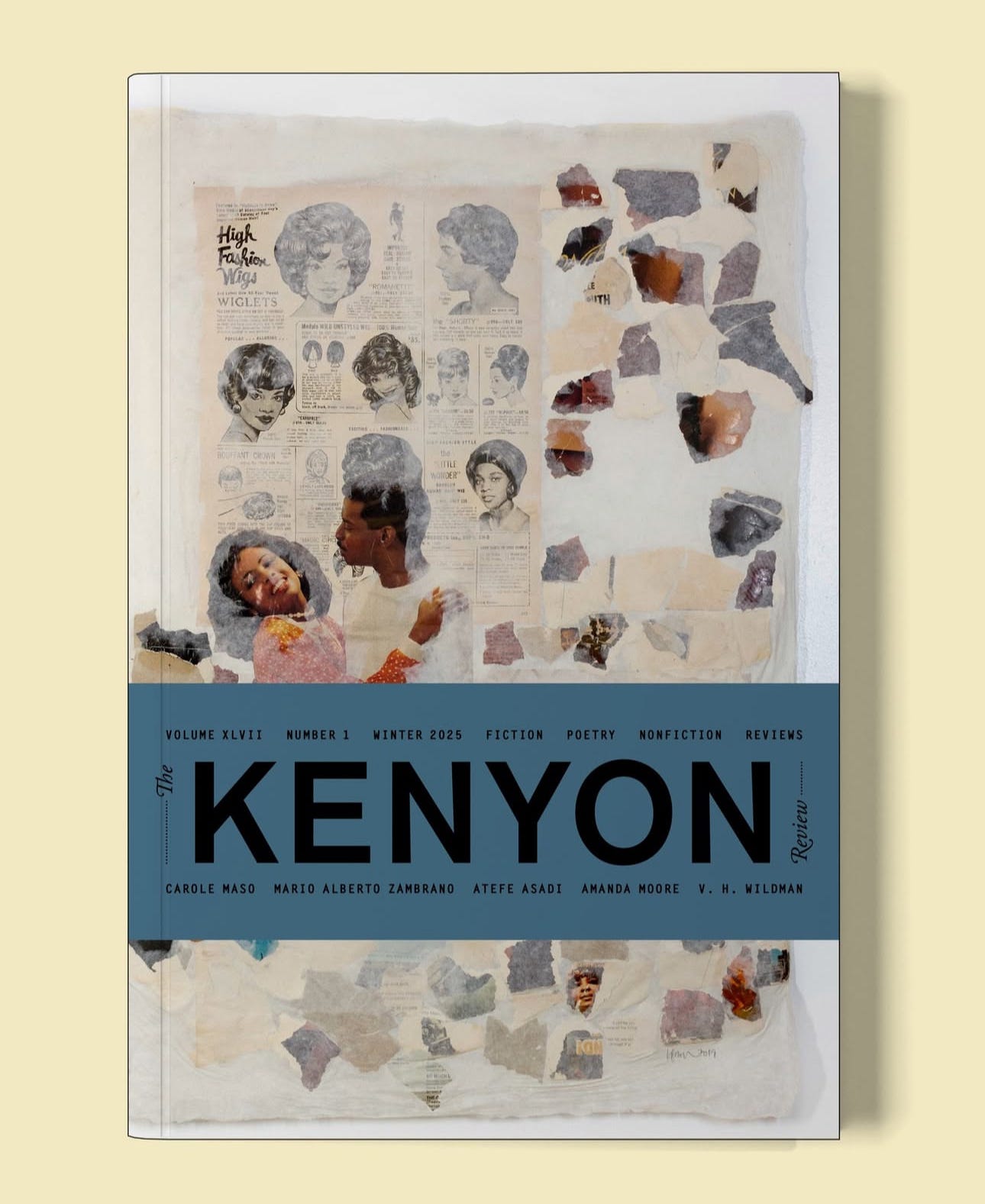

But then it did!!!! It won! And now you can read it online here or order a copy of the Kenyon Review’s beautiful print edition here.

This still doesn’t feel like the kind of thing that happens to real people. But it also feels like the kind of thing my mama would have believed could happen. That she believed it would happen. That she made it happen. Inside the incongruity of loss there are so many things I find myself suddenly ready to believe.

The introduction to The Kenyon Review’s Winter 2025 Issue is below. It would mean more than I can say if you would to take the time to read this too.

May we find pockets of wholeness this spring,

Jessie

The Kenyon Review’s annual nonfiction contest was judged by Melissa Febos, acclaimed author of four books, including the national bestselling essay collection Girlhood, which has been translated into eight languages. From this year’s entries, Febos selected “On Molting” by Jessica Petrow-Cohen as the winner. “At once taut and discursive,” writes Febos, “‘On Molting’ draws an outline of grief by sketching the contours of a life unmoored by loss but kept aloft by humor and the pleasures of memory and the mundane.”

Amazing piece. Thinking of you and your mama today. <3 <3 <3

Your writing moves me in a way that I can’t describe but that I can feel. I’m grateful that I hear your voice narrating for me so that I don’t actually read the piece, I listen to you explaining it to me. The Kenyon victory is insane. Amazing.